posted: 2025-01-29

Spoilers for Final Fantasy 7

Final Fantasy 7, Mako Reactors, and Cerenkov Radiation

What you just watched was a pulsing of the University of Wisconsin’s Nuclear Reactor (best known as the UWNR) located on campus (not too far from the football stadium actually), recorded with permission of the reactor operators and staff. The reactor, a 1 MW TRIGA (Training, Research, Isotopes, General Atomics) reactor 1, is a research reactor in the Max Carbon Radiation Science Center which is used for training and educational purposes. Students take courses like Nuclear Engineering (NE) 234, a course for freshmen interested in eventually become licensed nuclear reactor operators, or NE 428, a reactor physics lab course where students can learn about phenomena that occur during the operation of a nuclear reactor (like how I was at the time of filming that reactor pulsing video!). TRIGA reactors in particular are the most common non-power nuclear reactors in the world. The UWNR is about 1 / 3,000th the size of a common commercial reactor, so even if the university wanted to use it to power the local neighborhoods, it couldn’t (it’s a point of contention, which is fortunately beyond the scope of this piece).

But back to the video, If you’ve never seen this kind of phenomenon before, where the reactor core suddenly glows a bright blue before the light slowly begins fading away, you might be wondering how safe it might be for me to stand up above the reactor core while this is happening. Am I in danger of severe health risks? Well, no. Not substantially. It’s not like they would just let students (especially undergraduates 2) studying this kind of nuclear reactor phenomenon put themselves at risk so recklessly, think of all the segregated fees they’d lose! And for what it’s worth, the EXPOSURE calculation (NOT dose calculation because the health physicists will get on my case if I don’t get the terminology right, JILLIAN), was a required portion of the lab report. Also, like, I’m here writing this whole piece so I’m pretty confident in my lack of double-strand breaks 3.

Final Fantasy 7's Opening Hook

If you’re anything like me, you might be fascinated by the way science is presented in video games and media and how it compares to the science of the real world. And if you’re anything like me, you might really enjoy JRPGs to a fault. And STILL if you’re like me, you’ve become slightly obsessed with Final Fantasy 7 for the last half-decade years given the incredible exposure it got during 2020 and beyond, and because you now need to be able to have at length conversations with your FFVII-loving partner. Being honest, I still haven’t beaten Final Fantasy VII, if only because the game crashed on me in the final dungeon, and I kind of want to restart it so I can understand and enjoy the plot more now that I know the major twists in the game. Even still, I already appreciate the game quite a bit.

I am not the first person to acknowledge just how entertaining and exciting the crazy opening sequence is, nor will I be the last, but, man what an opener. Of course, fictional acts of ecoterrorism are exciting in the same way completing a fictional heist might be: the stakes are high and the consequences are dire. But beyond the high-energy action sequences, the incredible FMV cutscenes leading smoothly into the gameplay, and the carefully constructed sense of tension derived from the interpersonal relationships between Cloud and the rest of Avalanche, I found myself drawn to another interesting concept.

As a Nuclear Engineering degree holder and a general “ionizing radiation guy”, I might have to be careful of how I phrase these sections just to ensure I don’t advocate for the blowing up nuclear reactors, ESPECIALLY when we consider the shelling at the Zaporizhzhia Power Station. Let’s state this cleanly and clearly: I do not advocate for blowing up nuclear reactors! There. Now that I’ve gotten that out of the way, Final Fantasy 7’s opening sequence is one of the most thrilling and engaging opening 30 minutes of gameplay of any JRPG to date because you blow up a MAKO reactor. Between Avalanche beating up baddies first thing off the train to bypassing security in order to infiltrate Mako Reactor 5, and later escaping while blowing it to high heaven is one of the most thrilling moments I’ve ever had in my many years of gaming.

However, one of the coolest things that I discovered playing this game is the idea of Mako Energy itself and its visual design. In the context of Final Fantasy 7, Mako is the liquid (plasma? 45) form of the planet’s lifestream, and is a primary energy source that powers the city of Midgar. This energy can be condensed into Materia or Mako Stones for the player’s later use when enriched to a high enough level. Over the course of the game, the Shinra Power Company is able to harvest this energy via Mako Reactors, including the one that Avalanche and company destroy in the first moments of the game.

For all intents and purposes, Mako energy is a model of many negative aspects of different forms of energy. These include its negative effects on the climate, surrounding ecology, and even its effects on people who have continued exposure to the energy itself. In particular, those who are exposed to Mako for prolonged periods can suffer genetic mutations, poisoning and eventually death. And why design something specific if there isn’t a payoff? Naturally, these negative traits of Mako for a dramatic moment later in the game when Cloud falls into a stream of Mako for an extended period of time where his soul and personality are suspended, requiring Tifa to revisit Cloud’s subconscious. While no current energy sources remove one’s entire soul from their body and suspends them between life and death, it is interesting to consider the idea of Mako energy being a stand-in for ionizing radiation. There is a clear parallel between the Mako Energy extraction process and a process that is present across the globe when operating nuclear reactors: the visible blue-green light.

IRL Historical Bits

Before we go any further in tying together Mako Energy and nuclear science, we ask a really important question: “What happens when a particle moves faster than the speed of light?”

Think about it for a moment.

Thought about it enough? Cool.

You might have some sort of idea that this idea isn’t possible. “How can anything move faster than the speed of light?”, I encourage you to think about ways where this might actually be possible, a particle moving fast than the speed of light. Think about the assumptions we often make when we say “nothing can move faster than the speed of light.” Use your imagination, even!

Truthfully, I’ve cheated you a little bit. This question is incomplete, and I’ll explain how in just a moment. But many scientists in the late 1800s and early 1900s were asking themselves similar questions.

Oliver Heaviside, known for his super cool step function among other things, predicted that a point charge (the electron hadn’t be discovered yet) travelling through a transparent medium would produce a cone-shaped wave when travelling faster than the speed of light in said medium. Ok, yeah cool and all, but so what? A little dot moving through a space making waves is intuitively clear for us today if you’ve ever seen something like a duck across the surface of a lake, but why does the shape matter? Well this conical shape is incredibly important; readers who know a thing or two about airplanes might be able to predict what I mean. We’ll return to in time.

It looks a liiiiiiitle like this, if you'd like a visualization

Everyone’s favorite nuclear physicist, Marie Curie, also discovered something really neato while working in the lab. During her experiments, she would notice a faint pale blue light emanating from concentrated Radium sources, however, for whatever reason, she chose to not study it further. Who am I to judge Mme. Curie for her research choices? She was already WELL DEEP into establishing the concepts of radioactivity that I use for my research on a daily basis. Many researchers continued to study this glowing phenomenon, but it wasn’t until 1934 when this pale blue light was fully observed under a controlled setting. One Pavel Cerenkov, did his research on a regular recurrence of pale blue light around a radioactive preparation that was submerged in water, and would later have this physical event named after him: the Cerenkov Effect.

Cerenkov Radiation

So, let’s talk about this pale blue light, the Cerenkov effect. As it turns out, the observation that this effect took place in water is crucial in understanding how the Cerenkov Effect actually occurs.

First let’s briefly talk about the speed of light. Commonly referred to with the letter c, the speed of light in a vacuum is approximately 2.997 × 108 m/s, and this is a universal constant. This value will not change. However, neither we as humans on Earth nor do people of Midgar live in a vacuum. We all live in on a planet that is full of oxygen, nitrogen, and other particulate, which means that the speed of light is just a bit slower than c, but only negligibly so. The fact is that, from the field of optics, the speeds of light in different materials are fractions of the value of c depending on the material itself. We can determine this value for any given medium, like water, by dividing the value of c by the observed speed of light in that medium n = c/vmeasured. These values, which are known as refractive indices and represented by the letter n, have been tabulated (i.e. are in a table, an engineer’s best friend). For example, it is known that the refractive index for water is 1.333, meaning that light travels 1.333 times slower in water than it does in a vacuum 6. We’ll put a number on this quantity, the speed of light when travelling through water, shortly.

From this, we know know that we could theoretically have some charged particles, like electrons for example, submerged in water moving at speeds faster than the speed of light though water. This threshold speed if you will, can therefore be found by the inequality v > 1/n where = vparticle/c. Essentially, this math is just saying that if the charged particle’s velocity is greater than the speed of light measured in the medium, then we will observe the Cerenkov effect.

As an example, since the refractive index for water is 1.333 (or APPROXIMATELY 4/3) 7, the speed at which the charged particle must be moving at to produce Cerenkov radiation must be faster than 1/(4/3) c, or 3/4 c (or 0.75c if you prefer a decimal) which is roughly 225,000,000 m/s or 2.248 × 108 m/s if you want a little more precision and compactness. The point here is that the charged particle is still moving very quickly. Fast enough that you have to consider relativistic means, but for now, we’re going to just focus on the basics 8.

So then let’s say we have a charged particle, like an electron, that’s moving incredibly fast, maybe around 0.7501c or a value just greater than the speed of light in water to the point where, as it travels, it produces photons that are ejected in a conical direction. If you recall earlier in the piece, I mentioned that our guy Heaviside, as well as airplane and duck enthusiasts might have an idea of what goes on here. The charged particles are moving so fast that they create an electromagnetic “shock” wave, similar to that of a sonic boom, but instead of a large burst of sound, photons are emitted. It’s these waves that travel perpendicularly to the conical wavefront that are the cause of the Cerenkov effect and Cerenkov radiation!

These photons will have different wavelengths (or ripples) that correspond to a continuous range on the electromagnetic spectrum specifically between the near-ultraviolet region to the visible light spectrum specifically peaking at around 420 nm. For reference, the ultraviolet region is roughly between 10-100 nm and 420nm roughly corresponds to blue light, which answers the question of where that blue glow comes from!

As these charged particles continue through the medium and eventually slow down, this light eventually fades as there are fewer and fewer photons being generated until eventually the particle is once again travelling below the designated speed of light for the given medium. That’s how the glow begins to fade as well.

In short, the light you see in the bottom of an open pool reactor is basically just a funny little electric dot that’s going really fast through water, so fast in fact that it makes a sonic boom that emits light and not sound. That’s really all it is.

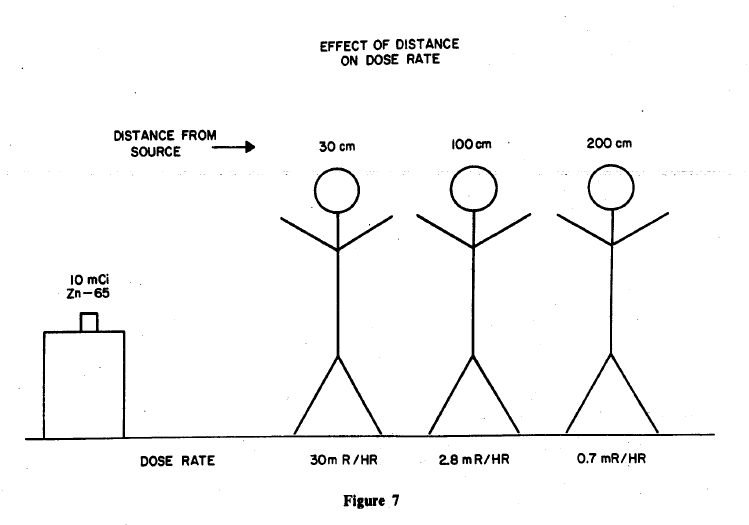

Yes, this light is emitted perpendicularly to the cone generated, which means that some of those photons will travel to the surface of the open-pool reactor where they might ionize some of the air around where I stand thus increasing the radioactive exposure in the space. But this exposure here is far less than what would be considered dangerous thanks to a few specific conditions: 1. the reactor core is ultimately enclosed, which is designed to shield the outside from significant ionizing radiation, 2. the core is submerged in water, which is a great general radiation shielding material, and 3. I am more than 5 meters away from the core, which is significantly greater than the mean-free path of a gamma ray (the average distance a gamma-ray can travel in a medium before it is absorbed) at 1 MeV traveling through water. This isn’t a case like with a rod of Cobalt-60 where if you can read the words “drop and run”, you’re more or less toast, it’s a safe phenomenon to observe provided one follows the listed safety standards.

DISCLAIMER

I am speaking incredibly broad terms since Cerenkov Radiation has a lot of other measures to consider that I won’t be covering in this piece.

For starters, “charged particles” could refer to a couple different particles including electrons, protons or muons, for example, and each of them have their own characteristics threshold energies that are required to generate Cerenkov Radiation. These energies vary and it’s possible to actually determine the types of particles based on the threshold energies required to produce Cerenkov Radiation, and is the foundation of the technology used in Cerenkov detectors 9 .

I haven’t really gotten into the specific health effects and shielding required in these cases because at this point, that’s a whole different piece that could be made. But to put it simply, the photons being generated have energy which can cause detrimental health effects if not properly shielded. Water is a common and very effective shield for gamma-ray radiation shielding for this type of application, which is the type of radiation present from the Cerenkov effect. Water is also a very effective neutron shield; those pesky neutral particles are the real villains when it comes to dosimetry, not gamma-rays 10. Water is an excellent thermal 11 neutron shield, and it keeps me, and the rest of my peers standing at the top of the UWNR safe from a significant gamma OR neutron dose. There are, of course, other ways to shield from gamma rays, and the TRIGA reactor system accounts for that. I’ve included a link to a fairly old article detailing shielding parameters for a TRIGA reactor, if you’d like to learn more. 12

I’m also not going to talk too much about the intensity of the light in this case, but a lot of analysis can come just from looking at the situation. The highest amount of energy are going to be around the areas where the light is brightest, while lower amounts of Cerenkov Radiation will be where the light is dimmer.

Tying back to Mako Energy

Now obviously Mako Energy is not just nuclear energy and the physics here in our world don’t necessarily tie back to the world of Gaia for one reason or another. One refutation one could make is how that the Mako energy seems to appear above the surface of the water as well, which would imply a difference in the physics itself. Obviously as well, there could be some kind of gasses present in the space as well, which could lead to the idea of plasma of some kind. Of course, I’m no plasma physicist 13.

But you can’t deny that there’s a pretty obvious similarity from a visual perspective. In my opinion, a glowing blue light at the bottom of a space with a given title of “reactor” pretty clearly translates the idea of some kind of radioactive mechanism occurring, regardless of whether or not the visual design team at Square had a conceptual understanding of Cerenkov radiation. If I had to guess, someone on the Final Fantasy 7 team saw a picture of a glowing blue reactor core, thought “that looks dope”, found out it’s a natural effect of radation and then thought “ohhhhhhhhhhhhhhh baby”.

Beyond this phenomenon, however, I don’t think there’s an exact parallel between Shinra’s Mako Reactors and the nuclear reactors we commonly see employed across the world today. The discussion of the reactor “design” is easily a topic for another time if I were so inclined, and I’m not gonna talk about the moderating and shielding properties of bricks that we see present in the Mako Reactor depths. Like dude, it’s fucking bricks. What are bricks made out of? Clay? I mean…. maybe that’s a fine gamma shield for Shinra… 14

I also won’t go into detail here about the motivations behind the design of the Mako Reactors, as, again, this could easily be an entirely separate study, especially when considering Japan’s history with nuclear power. It’s clear that these fictional Mako Reactors are meant to be villainous constructions people who clearly have no interest in preventing the climate collapse of the planet. I cannot say the same about when considering the advancements of nuclear reactor technologies. I hope that, if there’s one thing you can take away from this piece it’s that Cerenkov radiation is a normal physical occurrence that we understand and poses little-to-no-threat to the general public, reactor operators, or even curious students such as myself.

It’s just a tiny little shockey-type character moving at a speed faster than the speed of light in water which makes a visual sonic boom of gamma-rays. Bada-bing bada-boom. That’s your science lesson for the day.

post script

holy moly dude, do you know how fun it is to write about science when you're not limited to the worst, most inane passive language? Half the time I think the reason people get discouraged by the sciences is becasue no one in the community ever taughts a scientist how to make their work interesting to read. It's cool when you understand what's going on!

FOOTNOTES!

Yes, I actually shot this video in undergrad… five years ago… oh no….↩︎

that’s a radiation biology joke hahahaha↩︎

what the hell even is a plasma anyway?↩︎

that’s a rhetorical question, Idon’t email me telling me what a plasma is. i can go and ask my cohort and pretend to understand them just fine, thanks.↩︎

NOTE!!!!! I don’t want to imply that this refractive index is exactly 4/3, it’s actually a bit more akin to a sliding scale that has to do with the wavelength of the light, the ambient temperature, among other. That means that here the refractive index REALLY is just 1.333, which is kind of magical for us humans.↩︎

look I know that I said it wasn’t exactly 4/3 before, but damn it, I’m an engineer, not a mathematician. I’m going to make some of those calculations easier. I’m going to do math that I can look up in a table, and you can’t stop me. and honestly, it’s kind of funny since the mathematicians would be quite happy that I’m using exact fractions and not some namby-pamby wishy-washy three decimal number.↩︎

with the power of hindsight, i.e. editing this piece nearly two years after I initially wrote it, I can tell you that even if we did consider relativity here, there’s nothing that would necessarily change in the context of those problem.↩︎

Not my area of expertise, I do specifically gamma ray detectors. Lemme go talk to a pal o’ mine who can talk about them in greater detail.↩︎

not that gamma-rays are misunderstood creatures, they can still give you plenty of dose if you remain unshielded↩︎

low energy↩︎

again, please don’t reach out to tell me what a plasma is, i will block you with extreme prejudice.↩︎

found a couple cool papers on the effectiveness of red clay and waste glass in gamma-ray shielding. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2215016124001973, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9457075/↩︎